Introduction

The Meriah Song

Appeasement of the Spirit of the Dead

Lamentation for the Dead

Invocation to Goddess Chitagudi

Sloka to Exorcise Diseases

On This Sacred Soil of Ancestors

For the Dead Ancestors

I Offer you my Black Fowl

Friends and Brothers

Salt Business Fish Business

Voices Get Tired

The Thorned Bamboo

Come You All Snakes and Frogs

Intimacy, Ring to the Ear

The Siali Creeper

The Slender Beloved

A Rare Commodity

The Beautiful Narangi

The Sun Beats

The Turmeric Rain

I Float as the Eagle

Love, Roots Grown into...

The Anklets Jingle

If I Pinch Your Cheeks

Crown on the Head, Nose-ring on the Nose

Earth Sun Moon Be Witness

The White-haired Dhangda and the Dhangdi

of Empty Body

Mango Grove and the Sound of Water

Thieves from the Other Village

Tassels in the Wind

Saw Her on some Hill-Slope

You alone are Happiness

Those Lusty Young Men

Bringing along the Yams

Stepping down from the Marriage Altar

Sprinkling Turmeric Water

Introduction

Jadur Songs

Karam Songs

Jarga Songs

Japi Songs

Jatara Songs

Gena Songs

Adandi Songs

Introduction

Bakhens: The Ritual Invocation Songs of the Santals

Binti: The Song of Creation Myth

Kudums: The Santali Riddles

Hital

Love Songs

Marriage Songs

Baha Songs

Songs of Death

Miscellaneous Songs

Introduction

Come and Entwine Me, Delicate Pumpkin Creeper

My Sweet Grief

And He Did Not Dance

Come, My Rhythmic Fury

Words without Horizon

Emptiness

Sweet Agony

Bangles of Many-splendoured Rainbows

You are the Rain, Fill Me Up

In the Dance-hall of the Earth

Introduction

Mage Parab

Baha

Marriage

Love

Introduction

Sarhul

Karam

Jadur

Jatra

Marriage

Songs of the Fields

Introduction

Siran Uge: The Magician's Song

The Peacock Dances

The Empty House

Sweet-Potato Creepers

Useless as Dimiri Flower

O Spirit of the Hills

We are the Marat Leaves

White as a Crane

The Roads of Malkangiri

Appendices

Bibliography

Glossary

Index

Singing is older than speech. In singing the human being has always expressed his relatedness with his forces, with the totality of life. In his speech he expresses his relationship to things. Song is the primeval communion of all the ancient amicable-inimical closeness of nature whose pulse educated its rhythms. Speech is acquired separation ... Song is magic.

-MARTIN BUBER, Introduction to Kalevala

Men, patterns of moving dust, loving those familiar limbs, learned to think lovely curves, so tenderly shaped to receive and give, closed their long eyes, their things cooled in the tribal water and cooled their dreams in unending memory, endless year.

-FREDERIC PROKOSCK: Daybreak

The madal beats

Somewhere there, hidden.

The madal’s rhythmic

Continuous beat

Proclaims itself.

Is it not ashamed

To beat like this

Like a mad throbbing heart?

-A Munda song

In his "Appreciation" to Dennis Tedlock's Finding the Centre: Narrative Poetry of the Zuni Indians, Jerome Rothenberg observed:

Tedlock is an anthropologist who becomes a poet. By doing so he brings together two sets of concern with the tribal and "primitive" in human experience. The first - an older, nearly by-passed direction in anthropology - sees primitive cultures not as mere targets for objective study, but as series of communally structured and ecologically sound models, from which to learn something about the reorganization of society and the revitalization of life and thought. The second comes from the artistic avant garde (and behind or beside it, the political one), not in its orientation towards the future but in the parallel sense that it's rediscovering and keeping alive the oldest real traditions of man in poetry and art.

I have found in this the confirmation of a faith and concern which I have always held very dear. For more than a decade now I have had the opportunity of working among and knowing intimately tribal communities like the Mundas, the Oraons and the Santals and a number of other tribal groups inhabiting the hilly and jungle areas of Odisha, Bihar and West Bengal. As a Deputy Commissioner in two northern districts of Odisha, Mayurbhanj and Sundargarh, I had an opportunity to work among the Mundas, Oraons, Santals and Hos of Odisha between 1968 and 1972 and picked up their language. Later, on a two-year sabbatical on a Homi Bhabha Fellowship during 1975-77, I returned to the area for a more intense and intimate contact and study. I have roamed the hills and forests where these tribes live, stayed in their villages and participated in the rhythm of life in their villages. I have been moved by the intense and passionate character of their community life and the songs and dances that punctuate it. In my own way, I have tried to make myself an integral part of this rhythm. I have been lucky to have been admitted not only into performances of songs and dances, and other normal communal functions, but also to that strictly ritualistic and invocatory function to which outsiders are normally not admitted. I am grateful for the love and affection with which I was accepted into their community life and feel privileged to have been permitted to watch and participate in the ritual of even those more exclusive religious functions.

In this anthology are presented a selection from the oral poetry of some tribal groups of Eastern India. I have tried to present as large a variety of the oral song-poems as possible, ranging over subjects from love to death, from riddles to sanctified mantras, songs for social occasions as well as for ritual occasions. Ideally, one would have liked to present in translation the poetry of more tribes and more poetry from each of them and the present selection is only a small step in that direction. This anthology uses some materials previously published in the six anthologies of tribal poetry I have translated and edited earlier but a sizeable volume of fresh materials has been added.

The primitive poem or song is part of a complex of communal activity, which includes singing, dancing, religious celebration and celebration of social occasions. The songs, the dances and the relevant festivities are intimately and integrally related. For celebrating each important religious festival or socio-religious ceremony, the tribal’s have an appropriate set of songs and dances. It is necessary to view these poem-songs as part of such a total communal activity, which is not true of modern poetry.

The difficulties of recording and translating the songs are numerous. Firstly, the tribal is somewhat shy and withdrawn, and unless he is first taken into confidence, it is very difficult to get anything out of him, whether it is a song, a tale, or information. And you need all the patience in the world, the patience of a bird-watcher, not to try and force the pace. Slowly, by stages, by the intimacy and openness of your behavior and action, you can gain his confidence. And once you have crossed that threshold and are accepted you find him so different: so open, hospitable, friendly and intimate! The songs were collected partly by recording them at the time of actual celebration and partly by manually taking them down from the singers. There was no collection of songs in a simulated celebration. In this work, the assistance of local people and local tribal leaders was invaluable. Secondly, often the younger generation of singers are not acquainted with the background to many songs and Primitive Poetry as Love and Prayer the exact meanings of a large body of allusions, references and images which occur in them. It is only the singers of the old generation who know these and can also isolate the later additions or improvisations in an otherwise traditional song. Above all there is the question of language. Most tribal languages are unwritten: conventional from the point of view of usage but fresh and inventive. They are also highly musical. They contain a large number of symbols. It is necessary to retain in translation as much as possible of the symbolism as it is the essence of poetry. It is also necessary to preserve, as far as possible, the line-structure of the original. A lot of the music of the original, however, is bound to be lost for obvious reasons. The alliteration, the musical endings, the "meaningless" refrains can scarcely be retained. Often the same sets of songs were recorded in different villages to compare variations in structure, substance and style. Slight differences in the same group or groups of songs were noticed only when one moved a considerable distance away in a region or from near the urban centres to the interior villages. This was only natural and to be expected. The tribal communities are undergoing rapid socio-economic transformation and song-structures and song themes can't remain completely isolated from these developments.

The recognised performers remember the songs very well, particularly when they happen to be of the older generation. Most of the songs circulate by the process of oral transmission and their roots lie buried deep in the group-life of the tribes. There are no fixed song-makers and no attempt is made to take credit for having discovered or improvised any song. Most of the songs have come down from generations and performers learn them from their elders. The continuity of the old tradition is thus maintained.

It is true that, over the years, particular songs tend to get slightly altered. This, however, does not happen by any conscious design. While reciting the songs, one or more of the performers may suddenly introduce a new phrase or a single word or line which is generally appropriate to that song and it may catch on. The overall picture, however, is one of stability in the text and the formal structure of the songs does not change violently with time.

The poems or songs often accompany dances. The recitation of the words and the movement of the body are the two co-ordinates of the graph of socio-religious and ritual action which they define and describe. Curt Sachs, the noted authority on primitive dance, has said that, for the primitive, dance was a means of control over the surroundings. This endeavour to gain control over nature expressed itself through a psychological process of sympathetic transcreation. And the transcreation was a combination of bodily gestures, verbal symbolism and prescribed ritual action. For example, the Sarhul festival of the Mundas is partly a vegetation ceremony and also partly a fecundity ceremony. The ceremonial bath, the stacking of rice in baskets and the offering of rice beer to the village ancestors and using some of this rice for sowing is associated with fertility. It is thus an invocation for good and abundant crops. It is also an invocation for more members in the tribe, for more sons and daughters. The Sarhul procession is taken out to the village sarna, the village deity. The festival is celebrated by liberal drinking and dancing. The pattern of dancing thus gets integrally related to the text and meaning of the song and the rituals accompanying it.

The anonymity of the song-makers is a notable phenomenon in primitive society. The absence of a written language makes the process of transmission of the songs with their complex structure of social and communal association an amazing phenomenon. For the arrangement of words, the stylistic pattern and the grouping of images remain vitally unchanged over the years and this is largely because of this unwritten, oral character. "Anonymity in the present structure of society", said Robert Graves, "usually implies that the author is ashamed of his authorship or afraid of the consequences if he reveals himself; but in a primitive society, it is due to just the carelessness about the author's name.” This kind of carelessness is inherent in the primitive mind for what is important for him is the song and not the song-maker. To that extent he can be compared to the unknown artists, painters and sculptors who, in Konarka, in Khajuraho and all the world over, in sculpture, architecture and painting, have not left behind their names even while enriching the common heritage of mankind. The primitive mind does not know the emphasis on the ego, the "conceit" of the author which the twentieth century has brought so much to the forefront. The lack of any personal aspiration and ambition for name and fame makes these songs so much more genuine and authentic. The songs remain; the emotions they convey remain for the creator's sons and daughters, and their offspring after them. What more could the primitive singer wish for himself !

As I look back, I recollect wistfully how it all began, this involvement in the oral poetry of the tribes. It was a sparkling moonlit night in 1969 and the landscape, a lonely tribal village of Odisha lost in the midst of dense forests: the night of the full-moon in the month of Pous (corresponding to January) and one of the most important festivals of the Mundas. The lonely village street near the akhra was gradually filling up with the villagers. In groups they came, boys and girls, old men and women, dressed for the dance, humming tunes in high spirits. It was no longer the same village I had seen in the day-time - featureless, squalid and ordinary. It had been transformed by the magic touch of moonlight and the exuberance of spirit all around. They danced and they sang. Ancient, timeless songs. Old as the neighbouring hills, ancient as the moon. There were sprinklings of improvisations, and interpolations from the new world growing up around them: the world of development blocks, jeeps, village-level workers of government, fertilisers, insecticides and birth-control pills. The refrain line was "spring has come” and the following stanza's first lines were, in tune with spring's advent, "the koel has come", "the mahul and salflowers have come". But in no time they added on to these traditional lines others such as, "the babus have come", "the jeeps have come", etc. But these were mostly from the dancers of the younger generation. An old tribal sat by my side watching the dance, almost completely drunk, and looking very much lost. Suddenly he broke into song, like a winter tree coming into leaf. I can still hear the soft agony of that ageless voice and song. It was a part of that natural order, the lonely moonlit night of the empty mountains and forests, almost the voice of the night. Then I knew the tragedy inherent in the situation; the near-impossibility of integrating the tribal people into the greater society while preserving intact their cultural autonomy and individuality. It is only right that public policy should not treat them merely as museum specimens to be preserved, isolated and uncontaminated by modern society, in deep forests for study as "noble savages” by the scholars from cities. But may not socio-economic integration for the tribes bring about a cultural anomie, a drying-up of those sources of fulness of spirit, dark energy and exuberance that characterise much of the tribal way of life? May not their own oral tradition of songs be either forgotten, despised or hybridised by treatment with "insecticides” and "pills” by their own younger generation? May not acculturation and growing sophistication kill the authenticity of life, the art-forms and songs of these simple tribals? May not the more educated young men reject the very social milieu of which these songs and dances are the symbols? Certainly these songs deserve to be collected and preserved before perhaps they are sung no more and, maybe, die out.

These sentiments may be easily mistaken as nostalgia for a lost world, or a form of romanticised primitivism, and can easily be ridiculed as an attempt at reviving Rousseau's idea of the “noble savage”, of man who is born free and uncorrupted and is everywhere in chains, and being corrupted, the chains and corruption flowing from technological progress, prosperity and urbanization. It is as easy to romanticise the noble savage concept or the world of the primitive tribals as it is to ridicule them. Technology is not an unmixed blessing even for the primitive world and its socio-economic transformations. Nor is the cultural ethos of the primitive world always anti-progress or anti-growth. At least some part of the tradition and ethos of these societies could be selectively used for the development process. The path to economic progress and social transformation is not a fixed path. There are many roads to progress and many paths to Utopia. What is required is, therefore, a balanced view on the tribal world which can help resolve the mental ambivalence so common today among policy-planners, political leaders, social anthropologists and folklorists. The primitive world of the tribe, with its socio-cultural mores, its stagnating economic order, cannot obviously be frozen for ever. The law of social change renders this impossible. Contact with the larger community encysting these small tribal worlds will bring about transformations, whether desired or not. Hence the task for us is to find the mechanism which can marry the imperatives of technological progress with the preservation of the cultural autonomy of the group.

The world of oral poetry of Indian primitive tribes is an almost unexplored but vanishing world. Archer, Elwin and perhaps another handful of scholars have gathered and presented some of this vast body of poetry. But they have only touched the tip of the iceberg. Hundreds of thousands of songs remain undocumented. And what is more important, with rapid socio-economic transformation they run the risk of dying out or distortion beyond recognition. There are a very large number of tribes, each with a large volume of songs and literature. Even in respect of the three States in eastern India- Orissa, Bihar and West Bengal - there are nearly one hundred tribal groups. In Orissa alone there are sixty-two groups. What is presented here are only small selections from the poetry of seven selected tribes in these three States. The originals in transliteration in Roman script could have been given, but it was thought this would only increase the size of the book without adding much to the appreciation of the poems, as readers acquainted with the languages of the originals would be very few.

Far too long have the songs, the tales, the mythologies, the rituals and legends of the "primitive" tribes been treated as mere ethnological data; and, in an age of the assumed superiority of economic analysis of ethnographic materials, no wonder they are looked upon as somewhat residuary and unscientific and, in any case, of only marginal interest to the social anthropologist. This situation is not peculiar to India. It is a world-wide phenomenon. A time has come when it must be realised that, while we can speak of stages in technological growth, the same cannot be said of growth or efflorescence in the field of culture. There is no linear growth in the cultures of societies and all aspects of culture may not be susceptible to economic analysis. And the word "primitive" itself is somewhat of a misnomer. The Aztecs, the Mayas were also perhaps "primitives" from this point of view. Levels of culture are not proportionately related to either levels of economic affluence, personal incomes or levels of consumption or the capacity of the individual as a waste-maker. Social anthropology has to view these data as extremely significant tools of analysing personality traits, normative attitudes and social actions and behaviour-patterns. Scientism, whether of economic or political anthropology, can be a fallacy if not seen in the perspective of social processes, personal responses and inter-personal relationships. Further, it is high time we realised the immense value of these songs, legends, mythologies, etc. as literature per se. The absence of a written language, a script or proclaimed authorship of the songs or narrations do not in any way detract from the excellence of the songs or poems. All the songs/poems in this anthology are in fact anonymously authored. But, as Robert Graves stressed, contrary to the situation in modern societies anonymity is favoured not for avoiding guilt or embarrassment but because of the absence of a heightened ego which would claim all art-creation as that of the individual creator.

A word about the arrangement of the chapters. Two modes were available: thematic or community-wise. The songs could have been placed under different broad headings such as life-cycle songs or poems (birth, marriage, attainment of puberty, death, etc.), ritual songs (specific invocations of gods or goddesses), festival song (songs specific to different festivals, both agricultural and others, occurring during a year), cosmological songs (about myths of origin, migration, wars in historical times, etc.). Songs relating to different tribes could have been brought under thematic umbrellas. It was, however, for this anthology thought more appropriate to group the selected songs tribe by tribe. There are advantages and disadvantages in both methods. The method adapted here, it is believed, can give a reader a somewhat integrated view on the attitudes, mores, values and approach to reality of a particular tribe when a selection of the songs of that tribe is under one focus. A brief introduction to the songs of each such tribe is given not so much to present the cultural background "essential" to the understanding of the poems, than as mere introductory remarks on the group concerned. Learned discourses on the culture of a tribe is as relevant to the understanding of its poetry as would be the socio economic picture of Kalidas's times to the appreciation of his plays. It is, however, not denied that some poems have a particular "cultural context" and some basic awareness of the tribe and the main contours of its culture would help such appreciation.

Writers and poets, as also ethnologists and social anthropologists, have paid very little attention to "unwritten" poetry. Way back in 1940, in his Foreword to W.G. Archer's The Blue Grove, Arthur Waley lamented this inadequate attention to a very vital sector of primitive life and communal organisation. He said:

Another proof of the lack of work upon traditional song is the fact that when in 1934 the Anthropological Congress was held in London, out of nearly a hundred papers there was not one which dealt specifically with song. It may of course be said that song is not a detachable, independent subject, and is bound up with music, dance and other activities. But there were scores of papers which dealt with much narrower subjects; there was one, for example, on Aspects of Dentition.

Or take another test. I possess about a hundred and fifty books on ethnology, Only four or five of them mention singing, and there is not one which treats of it at all adequately.

That was in 1940. Forty years and more later the situation is not very much better. Tribal oral traditions have been, no doubt, studied and more of the poetry of the primitives published but social anthropology is still not very kind to the study of primitive songs as a method of sociological enquiry. Besides, these songs are not merely of interest as sociological literature; they have a lot of value as poetry. As regards Indian tribal poetry, Verrier Elwin's Folk Songs of Chhatisgarh, Folk Songs of Maikal Hills, Songs of the Forest (the latter two with Shamrao Hivale) and W.G. Archer's The Blue Grove, The Dove and the Leopard and The Hill of Flutes have made significant contributions towards understanding and appreciation of these folk songs and poems. In The Baiga, an ethnic monograph, Elwin made extensive use of songs as sociological "documents". As a matter of fact, poetry and ethnography are inseparable in this wonderful work. Archer's translations of Oraon songs in the two anthologies referred to follow the technique of Arthur Waley's brilliant transcreations of Chinese poems. The Blue Grove contained some of the finest translations of Indian tribal poetry I have seen to date. They were done with a great deal of delicacy and reveal a high sense of intimacy with the Oraon way of life and sensibility. Mention may also be made of Hem Barua and Gopinath Mohanty's contribution in this field. Barring however, these and a few other works, the picture, unfortunately, remains as bleak today as in the forties.

There have been no systematic attempts to document the oral poetry of the different primitive tribes all over the country. Analysis of the songs, the myths, the tales, the legends and the riddles can follow, but the first task is a systematic collection of these data which run the risk of vanishing into oblivion by sheer disuse and neglect. In each tribal group, generally speaking, the younger generation which has got the benefit of modern education tends to look down upon participation in the songs and dances of the tribe. Eager to climb the socio-economic ladder, they forget the lore of the tribe and, with the passing of the generations, certain songs also die and nobody knows them. Even within a decade I have seen proof of such extinction in particular tribal villages. In 1978 nobody knows or remembers a song which was recited with gusto in 1970 as the main voices, which had been those of a few old men, are no longer there. It is therefore, essential that we collect all the traditional songs, myths, stories, riddles, rituals, and cosmologies as early as possible, systematise them and analyse them, not only as oral literature but also in relation to value-systems, social structures, personality traits and symbolic milieu.

These oral poems are highly concrete in their treatment of theme and generally refer to some specific aspect of community life, its myth or symbolic structure. In a sense, the entire community life of the tribal is a very intense and uniform symbolic milieu. There is, therefore, no problem of communication, no difficulty of aesthetic distance that burdens so much of modern art and poetry. For us in modern society the symbolic milieu has been completely fragmented. The mythical universe is no longer part of a living tradition in most urbanised communities. When attempts are made to resuscitate the myth there is a genuine risk of its appearing as part of cultural anthropology rather than literature. This, I believe, is the difficulty in Eliot's poetry. The Waste Land goes back to The Golden Bough and From Ritual to Romance but society no longer understands or, rather, is no longer immersed in, the living myths of the tribe. It is, therefore, at best, harking back to an academic tradition; at worst an attempt to bring in too much of cultural anthropology. The difficulty of a return to myth and to myth-oriented literature, so extensively attempted by Eliot and Pound, and given such stout critical support by Professor Northrop Frye, is precisely this: the roots of social consciousness in the West are no longer in those fertile, dark and primitive unconscious realms. But to the Munda, the Oraon, the Kondh or the Parajas the myths are ever present realities. Their poetry, therefore, is very much concrete. Take this Munda song:

Dreaming of you in bed

I woke and took to the road.

Stumbling the stone

On the village-road I remembered

I remembered my caste, my gotra

And stood transfixed.

The obstacle to love here is not merely a mental block. The stone is not merely physical; it is mental itself. The stone marks the point where the remains of the ancestors lie buried, the symol of kinship and gotra. So when the boy stumbles on the obstacle, it is also a mental block. The stone is the ancestor and thus the song expresses very concrete despair. As if the stone says, "No it cannot be" ____and this denial may be more insistent and forceful than oral objections of parents in a traditional society.

In all primitive songs words are only part of a complex grouping of communal activities, namely, religious or social activities and dances. The accompaniment of dance with regular patterns of body movements or mimetic gestures with supporting actions like clapping or stamping of feet influence the pattern of the words. To this extent the songs which are merely the word-patterns lose something in standing alone without the music and the movement. In the words of C.M. Bowra:

The pleasure is not so complete as it might be if we enjoyed the whole, proper performance, but in isolation the words give the intellectual content of the composite unity. They take us into the consciousness of primitive man at its most excited or exalted or concentrated moments, and they throw a light, which almost nothing else does, on the movements of his mind.

In his Preface to The Empty Distance Carries..., an anthology of Munda and Oraon poetry edited by this author, the eminent British poet and critic David Holbrook observed:

The songs, and the illuminating comments on Oraon and Munda culture belong to a world-wide struggle among men to try to find a sense of their identity, not in mere "nationalistic" terms, but in terms of how, since they live "in" their symbolism, they can find particular meanings and forms of "authenticity" in their own lives, in their own place and time.

The more I have worked on the poetry of the various tribal communities of the eastern region of India, the more I have been convinced of the truth of Holbrook's assertion. In the three decades since the World War II one important trend in literature and the arts is a pervasive sense of loss of meaning, an inability to comprehend reality, a growing sense of rootlessness and non-belonging and an overwhelming feeling of blankness, pessimism and despair. Such a mood may have its origin in a variety of factors which are deeply embedded in our sociological and historical situation. Whatever the reasons, this mood has brought literature and art almost to the brink of an abyss, to a point where another step would commit us almost irretrievably to nihilism, moral cynicism and the death instinct. A period of rapid technological change, social transformations and urban explosion always has an unsettling effect on the cultural pattern. And the last five decades have possibly witnessed far greater revolutionary changes both in the structure of society and the material world than in any comparable period in human history. It was Pasternak, who had cautioned us that in an age of speed we must think slowly. Unfortunately, our generation seems to have almost lost the capacity to think slowly and effectively. This mood in art and literature has its effect on style. There seems to be a growing devaluation of the need for cohesiveness and lucidity in expression; an almost pathological obsession that the medium employed by the artist is no longer effective to express his complex fate and, therefore, true art today has to choose between silence or a form of broken Becketian expression that reflects a broken distorted gestalt. This is a total negation of the validity of art and literature and their relevance to our times. Life is meaningful only as the arch of a rainbow whose extremities are hidden away in the unseen past and future, in the incomprehensible timelessness of death; only as a span of relationships bridging an endless expanse of despair. It cannot have meaning apart from the colourful, inter mediate fleeting arch of the rainbow. Authenticity in art and literature, as also in life, consists of this ceaseless quest for what Martin Buber calls "the significant other".

In a pluralistic society the autonomy of the cultural groups constituting it needs to be preserved and strengthened. This strengthening cannot, however, be achieved either by looking upon the primitive communities as museum specimen to be retained tucked away in valleys and hills and to be studied by the "civilised” scholars from the cities, or by seeking to assimilate them into the melting pot of the larger community encysting them. The healthy attitude should be to see them, as Rothenberg observes, as a “series of manually-structured and ecologically sound models from which to learn something about the reorganisation of the society and the revitalisation of life and thought."

In these societies there is poverty but there is no public squalor. A Santal house, for example, is the last word in neatness and order. The delicately carved bamboo-rods used by the Kondhs to keep their tobacco can be the envy of any artist. Tragedies abound but there is no disgust for life, no turning back on it. There is no fashionable pessimism. At a time when it seems to require courage to say that man can be happy, the life-view of these primitive communities has a special bearing for us. In his Introduction to The Wooden Sword, one of the anthologies of Munda songs edited by this author, Professor Edmund Leach referred to this:

They do not seek consolation for the inevitability of decay by looking forward to a blissful rebirtn, in an imaginary "other world". Renewal is here and now in this world, in the quickly fading blossom of the jungles and the adolescence of our own children.

Life for the primitive tribes may be cruel and hard. Occasions of celebration, of festivals and joy, only briefly punctuate a life otherwise burdened with poverty, undernourishment and exploitation. But still, life is looked upon as an opportunity, and all activity as a thanksgiving for all the beauty and sacredness of nature, the hills and the valleys, the rustling streams and flitting butterflies. Many tribal songs have, no doubt, no purpose other than enjoyment; quite a number have an ostensible social or ritual purpose; but the largest number are concerned with the quest of beauty and holiness, of dreams and fantasies which transform the sordid ordinariness of daily existence into something rich and strange.

Of the large number of tribal groups inhabiting Odisha, Bengal and Bihar, at least seven have a fairly large body of oral literature, including poetry, which needs to be properly documented and analysed. In particular this is true of the Mundas and the Oraons, the Kondhs and Parajas, the Santals, the Hos and the Koyas. Some of the songs are of a narrative type; others don't tell a story but refer to some significant mood, situation or emotion. Narrative poetry largely relates to the cosmology of the tribes, their historical origins and migration in historical times. More important than these narrative poems are the poems associated with the festivals running through the cycle of seasons and rituals like birth, naming ceremony, attainment of puberty, marriage and death. The festival songs and a large number of the ritual songs usually accompany dances. As such, the melodies of many of the songs can be transcribed in regular musical notation. Working on the melodic patterns of the tribal songs of Eastern India, an eminent Hungarian musicologist, Dr Rudolf Vig, has found close similarity between them and gypsy music. He has put forward the interesting hypothesis that many tribal communities of India were possibly the original settlers of Eastern Europe around the Caspian sea and migrated to India many centuries ago.

These poems or songs can be considered from various points of view. Since they are meant to be sung they are often susceptible to expression in musical notation. The scores of a few songs have been provided in the appendix to generate an interest in this area. Secondly, the song-poems can be analysed also from the point of view of literature, their excellence as poetry. Often it is a poetry of symbolism and extended metaphors with a freshness all its own. Thirdly, often they have a ritual, social or religious purpose, be it the celebration of a phase in the agricultural cycle, a life-crisis or a normal social function. Fourthly, dance numbers generally accompany them and they deserve to be studied also from that point of view.

Like all oral literature, these tribal songs also undergo a number of distortions over a period of time. Among the distortions which are common to oral poetry mention may be made of the incorporation of stray lines composed of words borrowed from the events and situations in the context of development efforts in the tribal areas and the changing tribal scene. In traditional Baha songs of the Santals, for example, I have earlier referred to the incorporation of a line like The Babus have come, they have come in a jeep, to rhyme with the line, spring has come, welcoming the first flowering of sal and mahul trees with the advent of spring. Secondly, the traditional songs also tend to lose the wealth of old associations of peculiar, archaic words and are modernised by new composers. This has happened to Oraon songs and also, more significantly, to kondh songs. In the early forties, the well-known Oriya novelist, Gopinath Mohanty, collected the songs of the Kondhs of Koraput. He fully translated a number of them into Oriya. In respect of others he provided only gists. Thirty years later, it has not been possible to get at the meaning of all the words of the original songs even in the Villages from which these songs were collected. Being an oral tradition, its strength lies in authentic oral transmission from generation to generation, and as such disappearance of certain words, subtle nuances and lines from traditional songs is not to be wondered at.

The most fascinating aspect of tribal poems is their symbolism. Owen Barfield in his Poetic Diction puts forward the interesting thesis that poetic diction is nothing but the primitive, undifferentiated state of language, when objects are identical with, and non-distinct from, the bundle of associations they give rise to. This is the key to the understanding of the nature of symbolism in tribal poetry and its basic difference from symbolism in modern poetry. Basically, symbolism in modern poetry is an attempt to look for the unfamiliar, the concrete and the strange in a world excessively devitalised by the drabness of familiarity and generalised abstractions. It tries to break the stranglehold of the referential, representational and discursive use of language in everyday use. The world we live in is not the symbolic world of the primitive. It is mapped out, connected, intelligible. A sense of wonder and awe is discounted. For the primitive, on the other hand, social communication is itself part of the vast symbolic milieu in which he swims as a fish. The strange and the unknown peer out of everything and language is a method of gaining some control and direction in such a world. In a sense the entire linguistic structure is symbol. This can be illustrated by any number of poems in this collection. For example this Munda song:

The mahul tree

Full of branches and leaves

How it made the paddy field look lovely!

They are cutting away the mahul tree.

You five brothers, save it, save it!

Here the subject is not at all the mahul tree. It is the girl who has been given away in marriage. The village will look desolate when she is gone. And “they” are the members of the bridegroom's party. All this is never stated but always understood. Further, the brothers are not really expected to drive away the bridegroom's party. It is only a mock protest and a reference to the brother's role as the sister's defender in that society.

In an Oraon poem oranges are very cleverly used as sex symbols for a girl's breasts and the ripe, raw and half-ripe are described as being "too sweet", "too sour" and "sweet-sour" respectively. This can be compared to the Maikal Hill folk song:

He saw ripe lemons on her tree

How could he control his hunger?

In another Oraon poem:

To a tree full of fruits

Come birds to peck

Crows, pigeons, doves

And they chirp and frolic

The tree is the house of a man who has a number of marriageable daughters. The girls can also be sweet-smelling mallika flowers. The girls of village Diuri and Surmali are, in a Munda dance number, compared to ludam and champak flowers:

How nicely they bend down

The ludams of Diuri

How sweetly they wave in the breeze

The champaks of Surmali.

When moving in a line or running in a curve

What a necklace do they weave.

This kind of hidden symbolism in what is called the "clue” poems, is quite common in Mundari and Oraon folk songs but not in Kondh or Paraja songs.

The following Munda poem makes an interesting use of sexual symbolism:

Red alta on your feet

Yellow turmeric on the palms

Which alta field did you enter

Whose turmeric field did you go to?

Tell me truly, dear,

Did you enter a house of turmeric

In Munda and Oraon society red is often a symbol for life, energy and sex. The sindur or vermilion mark on the forehead and in the parting of the hair is a symbol of married life. Red also stands for blood. Similarly, turmeric has associations with marriage and loss of virginity. Entering an alta field or a house of turmeric, therefore, suggests loss of virginity or sexual intercourse.

In the Munda poem the "well" is a symbol for the girls sex:

There is a well at the end of the village

Its brick walls shine and glitter

……………………………………………………

The bucket went down and down

The poor girl how she wept

And wept

The well in tribal society is very much of a social institution. It is the club for the village women where they come to fetch water and exchange the gossip of the day. The well is a trysting place for lovers. But it also is often used as a symbol of the female sex as in the earlier example. A Gond song upbraids a girl:

O little well, you give no water,

Your youth is past

Think well, your youth is ended

While a Dhanwar song says of a girl who has come of age:

She still

Looks like a parrot

But the well

Is full of water now.

According to CM. Bowra –

…in most modern symbolism a symbol may indeed embody much that is important to what it symbolises, but it is separate from it, as the Cross embodies many Christian associations but is not the same as Christianity. But primitive symbolism asserts a real identity, The whale and the womb, the roots of a tree and the male member, are treated if not as exactly identical, at least as different examples of a single thing, which is both natural and supernatural and perfectly at home in the familiar works.

There are two other techniques of using symbolism which need to be mentioned briefly. In the first technique the comparison is put side by side with the statement of the song, as in the old Chinese poem quoted in translation by Arthur Waley in his Introduction to W.G. Archer's The Blue Grove:

The pelican stays on the bridge

It has not wetted its beak

That fine gentleman

Has not followed up his love-meeting.

This technique can be seen in the following Oraon poem:

When the paddy stalks are full of sap

The grains mature and ripen,

The pigeons come crowding.

I have a grown-up daughter,

And friends and relatives

Even from distant villages

Come crowding to my house.

In the second type the entire statement is through symbol, without any clue. It is only at the end of the poem that one or two lines occur that suggest what the symbol stands for. No parallelism is worked out, unlike in the first technique. In the following Mundari poem, until the dire consequences are mentioned, we do not suspect that the "mad dark bees" are love-lorn young men:

The glistening white mallika flowers

Blossoming in your garden

Invite the mad dark bees;

When the flowers fade

And the aroma is no more

The bees will vanish;

If they are caught send them

To the Keonjhar cutchery.

While analysing the symbolic structure of tribal poems we will do well to remember the essential social purpose they serve. Since tribal society is much more of a symbolic milieu than ours is, there is no hiatus between poetic symbolism and social communication. Verrier Elwin rightly observed,

A symbol is the readiest cure for embarrassment and can smooth over a business transaction or a hitch in one's love making with equal facility. So when emissaries go on the delicate business of arranging a girl's betrothal they do not state their purpose directly, but say they have come for merchandise, or to quench their thirst for water, or seek a gourd in which to put their seed. Similarly, the whole intricate absorbing business of daily love is carried on with symbols. Women by the well ask each other, "Did you have your supper last night?" "Are you weary from yesterday's rice-husking?" Men speak of digging up their fields, getting water from the well, entering a house. Not only the solicitations of the seducer but the domestic arrangements of wife and husband cannot be decently conducted without a verbal stratagem.

In comparing Oraon love songs to Baiga love songs Archer says that “If we define a love-poem as the expression of rapture Baiga poems are as obviously love songs as Oraon poems are not". The Mundari, Kondh and Paraja love poems are real love poems in this sense. The Kondh love songs probe even deeper as in the example below:

Beloved, dear,

How fickle, how impatient you are!

Only the flash of a face

A streak of lightning

In a moment you fade in the dark;

The distant firefly, coming near, no more.

A Paraja love song goes even deeper in its musings and sees love and death together:

You are eternal as death

The fear of death and your love

As intimate neighbours

They inhabit my dream

And so I play with life

Or

You are the rain, the new bride

The raindrops are you

They fill me up.

Or

How beautiful is the golden phasi

Down the bridge of your nose

Pining for that face

The brass string of my dung-dunga weeps

How sweetly it rings out the agony

The bare, naked voice of grief.

In many of these poems one can also notice a peculiar obsession with the passage of time. Time is not merely a sequence of seasons; or cycle of activities; it is also life and death, pain and pleasure. For example:

Asadh comes

And how she goes!

And where?

Where does Time go?

It comes - only to go?

And time is also Death, its ceaseless watch on life to be captured:

At your back

Death watches you

From dawn to dusk

He keeps a watch on you.

The Kondh poem refers to the world as a dancehall of men, a "dhobi-ghat", i.e., a place where washermen wash soiled clothes.

Life, for the Munda, Oraon, Kondh or Paraja, is not all dance and song. Dances and songs do punctuate their lives but tears lurk not very far behind those joyful faces. Different forms of anxiety obtrude. They are not merely economic or social. There are personal tragedies; love is not returned; a girlfriend or a wife deserts, naked and brutal reality threatens:

Speak no cruel words to me

My dear

How my heart pines for you,

Great is our misery

My parents have no money

To offer as kanyasuna.

As the bamboo tree dies

Swaying in the wind

The poor Paraja dies

Driven to grave by ceaseless labour.

The pumpkin plant's tragedy is from the day

Two leaves shoot forth from the seed;

Men pluck them out.

Man's tragedy is alike:

From childhood

Useless iron is thrown into corners

The poor man enters the forest

Crow-bar on the shoulders

Basket on the head

And life, only a tragic song.

But tragedy is often endured with a smile. It is sometimes even scoffed at. The primitive is very sensitive to the incongruous and the absurd. He can laugh at practically everything, including himself. Here is an example:

The co-fathers-in-law come

Like a pair of bullocks

They have drunk at the hat

And come back together

Like a pair of bullocks.

The two drunken old men (father of the bride and of the bridegroom) walking like a pair of bullocks is certainly a hilarious subject

Or this stubborn, outspoken refusal to marry:

Oil and turmeric

I will have none

Never on my body

And don't tie up flags

Of waving mango leaves

I will not marry the black girl

Of this wretched village;

Do you hear, friends?

Never shall I marry that black one!

But at the end of all pain and misery there is thankfulness for the very fact of being alive. As in this Kondh song of an old man on the day of Pous Purnima festival:

The old hearts still beat

And we are alive

Here in this ancient village

Of dead ancestors

And so today we could partake

Of this great jubilation.

It is here that these tribal poems so much resemble Chinese poetry in their outlook and tone. Of Chinese literature, Arthur Waley said that it “excels in reflection rather than speculation". As in Chinese poetry, here one finds such a lot of creative delight in experience; such a lot of courage in accepting reality without any dramatisation, idealisation, or rationalisation. In his Introduction to Plucking the Rushes, an anthology of Chinese poetry, David Holbrook refers to this resignation, not despair; this transcendence of envy; the gratitude for the continuity of life and love in Chinese poetry that puts sufferings in the larger perspective of human existence set among the indifference of the natural world. This is where it differs, he rightly holds, from modern existentialism. These tribal poems reveal a similar attitude of a mind which is aware of pain, in fact writhes in pain, but refuses to curse or run away into despair. Albert Camus once said that "all great art extols and denies the world at the same time". The simultaneous celebration and rejection of the world by the simple primitives can perhaps have a lesson for us.

The invocatory songs of the Santals and the Meria song of the Kondhs are almost reminiscent of the Vedic rituals invoking prosperity and plenty for the community. For the tribals the supernatural world, the world of bongas, of spirits and dead ancestors, is as real as the natural and social world he lives in. There is a benign or evil god in the neighbouring hill, the flowing stream at the outskirts of the village, the sacred grove and even the domestic kitchen. These gods take an intimate interest in human affairs and their blessings have to be invoked by appropriate propitiatory devices. Here poetry and ritual go hand in hand and serve an intimate and important social objective.

In modern technological society, art has tended to oscillate between two extremes. It has either been treated as a packaged form of mass entertainment or as the concern of an increasingly small minority of elites that should more appropriately be termed a "priesthood". Maybe, avant garde art seeks to preserve the mysteries of art as a secret fiesta from the profanation of all-conquering technology. But it is not possible to forge a healthy relationship between art and society on the basis of such a narrow concern. Secondly, the production and consumption of various art forms in modern society are being regulated and controlled more and more by the economic gate-keepers, the producers of films, the reviewers and critics, the stage managers, the art-gallery owners. In primitive societies, these economic gate-keepers were conspicuous by their absence. Art is wedded to life, it springs from love and is woven into the structure of the daily ritual of living. There is a continuous linkage between action and dream, between manual labour --using one's own hands-and art-creation using one's intense imagination. The entire community participates in the joys and sorrows, the triumphs and tragedies. The individual is not the rootless estranged self suffering and the angst of alienation and the sense of non belonging that brings nausea, Tribal expressions of art, song and dance are governed by age-old customs, and by the employment of these forms, songs and rituals, the tribes keep alive their value systems, their creation-myths and time-honoured customs of their ancestors. They produce art because they must. The motivation for art-creation is none other than the passionate desire to express a sense of form.

There is yet another area in which the study of the oral poetry of the tribals, as also their other art-forms, can have relevance for us.

While the trend towards transformation of tribes into castes has lost momentum in India and steps have been taken to preserve the autonomy of tribal cultures, the thrust of socio-economic transformations has been modifying and reorientating traditional tribal cultures. The emphasis on tradition, mythology and a golden age in the past has acquired a new dimension in the context of socio economic transformations of the tribal societies. An important result of these transformations is the emergence of a noticeable group of power-elites within these societies who want to emphasise the cultural exclusiveness and uniqueness of the tribe and its tradition and mythology. Part of it is no doubt a genuine search for roots but it is also partly due to a kind of vested interest in resurgence and revivalism. But one has to look deeper, both into the social structure and the emerging social stratifications to understand the nature and direction of this new emphasis on cultural forms. Myths, symbols, oral literatures, religious beliefs, traditional values, no longer remain what they were; they have been revised, reorientated, sometimes even without a conscious design or sense of direction. Interest in culture becomes often vicarious, gratuitous, a part of the search for the new dynamics of acquiring and sustaining political power and status. And yet, superimposed on all these is an awareness of the "community", the small community. This itself surely holds hope in a world of growing impersonalisation and loss of individuality under the pressure of large-size organisations. Discussing the ritual processes not merely as a structure but also as an anti-structure, Victor W. Turner refers to their role in achieving communitas, which is basically an egalitarian relationship between persons stripped of status and property. In discussing the formation of the Franciscan Order in the Middle Ages he quotes M.D. Lambert (Franciscan Poverty, 1961) that Francis was a "supreme spiritual master of small group; but he was unable to provide the organization required to maintain a world-wide order." This is where the tribal culture as a small community can serve as a model. Martin Buber observed:

An organic commonwealth - and only such a commonwealth can join together to form a shapely and articulate race of man - will never build itself up out of individuals, but only out of small and even smaller communities; a nation is a community to the degree that it is a community of communities. (Paths in Utopia, 1966).

It has been typical of Indian social organisation that it has always sought to create such a living and growing community, which is in essence a community of communities.

Secondly, among different models of integration of tribal culture and society with the larger society emphasis was so far placed only on the theory of a melting pot with constant give-and-take and cross-cultural co-existence. The time has come also to emphasise the search by the tribes for universal human values inherent in their own cultural matrix. The search for the great tradition, for abiding historical values transcending the demands of here and now, point to this. This is a positive sign for cultural growth and efflorescence vis-a-vis the arid confrontation or withdrawal of earlier years.

Thirdly, and this is most important, there are signs of an emerging force of counter-alienation in this new search for cultural roots by the tribal groups. Over-emphasis on ethnicity leads to a drying up of sources, an anomie grows in the heart. Tourain has rightly told us that

today it is more useful to speak of alienation than of exploitation; the former defines a special, the latter merely an economic relationship. Alienation means cancelling out social conflict by creating dependent participation. Ours is a society of alienation, not because it reduces people to misery or because it imposes police restraint, but because it reduces, manipulates and enforces conformism.

A genuine awareness and growing interest in tribal culture will sustain our commitments to universal values which emphasis community, instinct and imagination and may even help us look at the city as a conglomeration of neighborhoods or as Buber's community of communities with varying cultural patterns, beliefs and value-orientations fitted into a mosaic.

Examining various devices which may reduce and even prevent social confrontation and conflict, Coser suggests in his book. The Functions of Social Conflict, that mass culture and popular entertainment are primarily meant to provide a vicarious and safe release to hostile impulses. Institutionally, therefore, they are in the nature of a safety valve to release tensions. Directly and indirectly art helps bolster the morale of groups and helps to create a sense of social solidarity and unity; it may also function as a nucleus for organizing social action and social change.

The role of art in a primitive community is to identify a cultural field. This is something akin to what Marcuse identifies as the subculture in present Western societies existing as the Great Refusal or the posture of defiance. The continuity and universality of a culture is assured in a small community. Cultural conflict by way of formation of sub-cultures and contra-cultures is absent in such communities. A homogeneous culture can rise only in a small community.

A significant impact of the development of the Western conception of fine arts and culture has been a change in perceptions, so that the artefacts, dances, songs and the myths of the people all over the world, whose forms expressed aesthetic qualities, became “visible". Andre Malraux has rightly pointed out that

before the coming of modern art no one saw a Khmer head, still less a Polynesian sculpture, for the good reason that no one looked at them. It has now become possible to conceptualize various intricate aspects of primitive culture so that world culture may benefit from it. For to participate in the work of art is to reassert its existence as an object rather than as an individual personal expression.

This is apparent from the various studies on the theory of diffusion of culture and culture traits in such communities by Paul Wingert in his Primitive Art: Its Traditions and Styles. The small community makes the preservation of these expressions possible in a unique and authentic way. The distortions are less, the genuineness and true-to life character still predominate. This makes preservation of the authenticity of culture and its transmission a simpler and natural task, which in turn makes it all the more important that we who believe in unity in diversity should emphasise the need for maintaining small communities and their cultures, allowing them develop in their own unique ways.

One of the consequences of a greater awareness of the cultural traditions of the primitive tribes can be to induce us to step outside the prevailing climate of over-emphasis on cultural relativity that has encouraged cultural myopia and ethnocentrism. It can broaden our very conception of art. It is necessary to remember that the forms called art today were not perceived as such in earlier times or by other cultures. As we know, even in the western tradition one era sometimes did not understand another. For example, in the twelfth century no one really looked at Greek art. Similarly the seventeenth century almost totally disregarded mediaeval art.

Much has been said about the difficulty of translating poetry. This difficulty is all the greater when the poetry happens to belong to an oral tradition. In translating tribal poetry the major difficulty is how to retain the music. The songs generally have a “refrain” and a certain number of words occur at the end of each line. Carrying them over literally into English translation sometimes mars the effect. It is for this reason that an attempt has been made to retain as much of the pattern of the lines and the texture of the songs as possible. It is only rarely that deviation has been made from the structure or pattern of the stanzas and the songs. The music of such songs is much more difficult to retain. Often there is refrain line or lines which really do not convey any meaning but, because of their alliterative sequence, lend rhythm to the song in original. The poems in their original reveal an infinite capacity to invent onomatopoeic words and expressions. These sonorous phrases greatly add to the effect of the songs. Only a few of them may be mentioned here--ariari, ata-mata, bojo-bojo, chere-bere, chum-chhum, keleng-beleng, kere bore, kidar-kodora, rese-pese, ribi-ribi, tapu tupu, tiri-tiri. Similarly the free use of expletives like ge, go, ho, re, do, etc., the arbitrary lengthening of vowel sounds for the sake of euphony or emphasis and the insertion of short vowels in the middle of words or as suffixes to words adds to the melodic quality of the songs.

Apart from alliterative words which lose most of their music in translation there is also the problem of comprehending the structure of the symbols. Malinowski referred to the need for “the verification of the cultural context’’ in the translation of tribal poetry. In his words the translation of words or texts between two languages is not a matter of mere te-adjustment of verbal symbols. Poetry in the last analysis is a system of symbols, which are compulsive because of their vitality as images. Hence it must always be based on a verification of cultural context.

Further, there are certain words which, because of their archaisms and esoteric significance, are difficult to translate into another language. The images also sometimes partake of this difficulty. For example, when the lover is described in a Munda poem as "handsome as the arum flower", it becomes difficult to appreciate the significance unless one knows that the vigorous and yellow arum flower is a source of never-ending fascination for Munda girls. The beloved's body is compared to the flame of an earthen lamp. The woman "stands as a banana tree". Often she is mentioned as a flower or a dove without any overt reference to such a comparison being made.

In any language, and more so in its poetry, words are not merely sounds, they are also signs. "For the poet”, observes Jean-Paul Sartre in his What is Literature?, “language is the structure of the external world. The speaker is in a situation in language; he is invested with words. They are prolongations of his meanings, his pincers, his antennae, his eye-glasses." This is more so for the primitive for the simple reason that his language is less differentiated, logical and ratiocinative. In such a situation, the meaning of a poem of song remains peculiarly mixed up with its image-structure as well as its melodic pattern or rhythmic beat. The signs may often be the sounds and both may point to a vaguely felt impression which builds up to an image. Archer has discussed at length the difficulty of translating Indian folk poetry into English. Differences of verbal structure" he says, "are so great that if parallel images are retained, the rhythms will be different. If the rhythms are maintained the image will suffer, while no form of English can reproduce the musical effects of Hindi, Uraon, Gondi or Mundari.

But the rhythm is so powerful that in translation it also comes in to an extent or rather forces itself in. But where retention of rhythm or the original musical form in English demanded sacrificing or changing an image I have scrupulously avoided it and resisted all temptation either to poeticise it by adding in or omitting. Arthur Waley himself says, “Above all, considering images to be the soul of poetry, I have avoided either adding images of my own or suppressing those of the original."

For successful and authentic translation of the tribal song-poems, direct knowledge of the tribal language is no doubt ideal for the translator. Knowing Santali I have found it most satisfying to translate from Santali as also from the allied poetry of the Mundas and Hos. When, however, knowledge of the language is not available to the translator, the next best course is to take the help of someone who is well-versed in the tribal language. In this context I have noted with great satisfaction the translation of Mundari songs done jointly by Ramdayal Munda and Norman Zide of the University of Chicago. While Zide is a linguist and a capable translator, Ramdayal Munda is himself a Munda and also a linguist. Elwin's translations were perhaps less authentic as there were many attempts at poetisation. The native-born speaker of the local tribal languages on whom Elwin depended was obviously not as sensitive and as well-informed about the problem of translation as Professor Ramdayal Munda.

Ideally, it is perhaps necessary to give two renderings of each tribal song-one, a word-by-word rendering as per the line-scheme and another, a literal translation or paraphrasing. The first would indicate the peculiar syntactic structure of the specific language. Such an attempt has been made in the section on Koya song poems.

The structure of the songs, as also the arrangements of the lines, differ from tribe to tribe. Normally, the Munda songs are short and have a repetitive pattern, as in the following example:

The cut-away twig, mother

The cut-away twig

The cut-away twig never sprouts again.

The waters of the river, mother

The waters of the river

The waters of the river never turn back again.

The Koya songs are often longer, as also the Kondh songs. There is also a wide range of variation in the general emotional climate conveyed by the songs. While the Kondh songs are more serious and reveal a tragic sense of life, the Santali, Munda and Oraon songs are lighter in vein and often have a peculiar sense of irony, The invocation songs of the Santals are recited either by the village priest or naike or the head of the household. On the other hand, the general songs of the tribes are participatory in nature and the community joins in the songs, which also generally have their accompanying and corresponding dance-numbers.

In his Preface to The Empty Distance Carries, an anthology of Munda and Oraon songs edited by this author, David Holbrook observed:

In our civilization we are actually having to battle, to assert that man's primary need is for the significant other, to use a phrase from Martin Buber. And how much our London culture could learn from the deeply metaphorical eroticism in these poems, which contrasts so sharply with the new and infantile grossness that has overwhelmed us, making true love poetry almost unspeakable today in England.

Primitive poetry and art have thus a relevance not merely to literature but also to the quest for meaning and authenticity in the face of dehumanization of the arts and the resurgence of the libido and death-instinct in it. There is a crying need to re-emphasize the life instinct in modern art if art is not going to become totally irrelevant to modern civilization. It is in this sense that I feel primitive poetry has relevance today: not merely as "poetry" as C.M. Bowra had so ably analyzed, but as adding a significant dimension of meaning and purpose to the business of living and dying.

There is a world-wide awareness today that human life must be brought back to the hidden intuitive exuberance and zest for living that characterized human imagination in many earlier centuries. In his Age of Aquarius, for example, William Braden, speaking about the America of the future, poses this same question. Will it be blacker, more feminine, more intuitive... more exuberant and just possibly better than the America of the past? "It depends", Braden answers, "on the outcome of the struggle between the humanist and the technologist, both bent on reshaping society in their own ways" There is an inherent conflict here. It is no longer possible to keep in separate compartments the scared ritual and profane technologies, our moral fervour and scientific rationalism. But it is possible and extremely desirable today to find solution to the tension between what Braden describes as "those who wish to make the world a comfortable dwelling place and those who conceive of it is a machine for progress”.

Technology no doubt has to find an answer to the problems of poverty afflicting the primitive communities. But their rest for living, the inherent sense of communal solidarity and harmony with the natural world, are values which modern societies suffering from growing cynicism and lows of nerve, insipid individualism and the breakdown of the ecological balance, are perhaps desperately in need of fostering and developing. In the heart of modern technology as also of primitive rituals is an emptiness; in one case, the emptiness of being tired of life, in the other the emptiness of poverty and drudgery. Each has need of the other. The city must be married to the jungle and the new technology must be married to the lifegiving rituals and mythologies. That way perhaps lies the key to a new resurgent life-affirming culture.

The Indian primitive tribe’s world is immensely alien, not merely to the western world but even to the world of the urban elite in India. The songs/poem in this volume will, it is hoped, reveal some this strangeness not merely from the technical point of view of data or facts but also of the attitude and approaches, the values and the perceptions; in short of the mechanism of apprehending reality. Some of them may be even action-packed ritual but their beauty, freshness and occasional technical virtuosity remain to be envied. The emphasis is, however, not on the “alienness” or strangeness of this world or the strange modes of apprehending experience. It is more on the naturalness and case, the simplicity and grace, the elegance and absence of anxiety which characterize many of them. The emphasis, in short, is on the freshness of the images and metaphors, the authenticity of experience and the concern for community.

I have sought to prevent the poems as poems of today, living vital and warm, and not as dry ethnological data of complex and strange "primitive” world. Being a poet myself, I have tried to see and feel them as poetry and no other consideration has matter-neither enthology nor religious association or ritual significance, I can’t but conclude this note by quoting Brand on from his preface to The Magic World: American Indian Songs and poetry: “All that we want from any of it is the feeling of poetry. Let the enthnologists keep its ‘science’ and the cocoming generation of Indian poets its mystry.”

Here we Sacrifice the enemy

Here we Sacrifice the meriah

It was the golden sunshine of the last days of Pausa. Eighty-year-old Sarabu Saonta leaned against the sal tree at his doorstep and looked into the distance. The air was fragrant with the aroma of unknown forest flowers and mahua wine. Butterflies with multi-coloured wings floated like lamps in the golden sun. In the distance, at the end of the village street. The worship of Dhartani, the earth goddess, had started. Almost the entire village had gathered there. The houses and the village street were empty'. The rhythmic beat of the drum revived memories of his earlier days, and Sarabu started reminiscing.

He remembered his youth, his songs, the mad abandon of moonlit nights, and his girl friends of yester years, whom he used to call Nilas, Talas, Lember and Dumbar---those affectionate names which he had conferred on them while passing the night in the dormitory for the unmarried boys of the village. The unmarried girls had one also. His entire youth floated past like a dream, like the morning fog slowly unfolding layer after layer of the hills.

Sarabu remembered also his endless miseries and the miseries of his tribe. He was the Saonta, the headman of the village, dressed in a loin cloth, copper-coloured hair on his head, thick and dishevelled, a quid of tobacco-leaf always in his mouth. His Kondh religion told him that the King--the Authorities--happened to be the younger brother while the Kondh, the Paraja (the subject), was the elder bro ther. The younger brother was crafty and had snatched away the kingdom from the elder brother by dishonest means; but he did not mind. He had learnt to forgive. He was as tall as the hills, broad and expansive as the sky, somewhat uninhibited and impulsive.

Sarabu still gazed into the distance; the drums continued their rhythmic beat; the rows of houses stood vacant in the sunshine. Beyond these were the blue-green ranges of hills arranged like coloured palanquins. Range after range of hills and valleys: that was his beloved Kondhistan Down below, the gurgling hill-streams with their crystal-clear water; the yellow alsi flower everywhere and buzzing bees. Sarabu was ill. His whole body ached. There was pain in his chest, the murmur of the streams, muted, somewhere inside. But then he had lived so long; enough proof of the fact that in his previous life he had been a good man. For if he had been a bad man, he would have died much earlier. In his last birth, he must have done some good work and certainly in his present birth he had done no wrong to any body. He knew his physical body would grow old and be discared. His soul would go out and return in some other body to this beautiful Land of hills, flowers and streams. Death was only another stage in the eternal process of ever-returning life. The villagers, the people he knew, the green hills-everything would still be waiting for him; the streams would still be flowing and the sap of life would be still surging ahead when he returned. Sarabu confronted Death, face to face, but he had no worry. He had lived his life to the full, gone out on shikar, enjoyed his food, drink and tobacco. What did it matter if he died now? He was sure to come back to this beautiful landscape, the dazing valleys and the gurgling streams. He could not long be parted from the glory of human life.

Sarabu brought his flute from the house and, in the golden sunshine, of late Pausa, his flute called out the names of Nilas, Talas, Lembar and Dumbar. Sarabu danced as if he was possessed like the Kalisi or the Bejuni; as if the Nachini goddess had possessed him and he was worshipping the life-force with the last drop of his energy. Sarabu played the flute and danced. In the honey-coloured afternoon sun, the village dozed; dark shadows danced before his eyes and Sarabu dozed off finally on the most important festival day of the Kondhs.

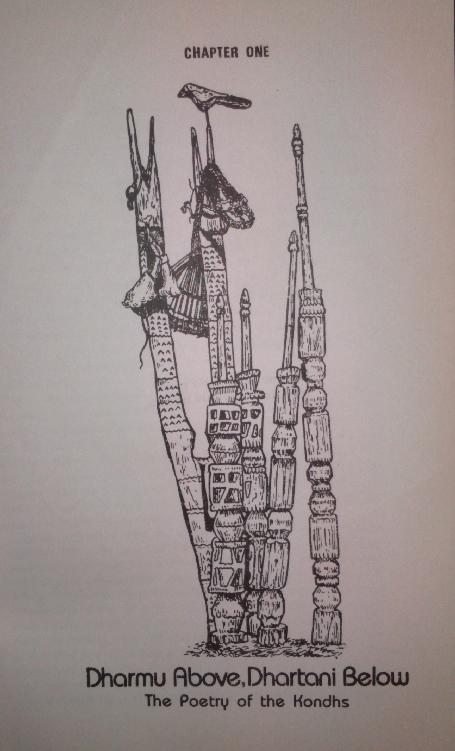

ABOVE: Dharmu the God of Justice

BELOW: Dhartani the God of Ancient Earth

common to perhaps the as an integs and calami dancing, 1

This is a translation of some portions from the opening chapter of Gopinath Mohanty's celebrated novel, Amrutar Santan (Sons of Nectar), Sarabu may be an imaginary character but he typifics almost everything that the Kondh culture represents: a deep attachment to and intimate love of life and the world, along with a painful realization of all the miseries of economic exploitation, deprivation and want. A deep sense of mellowness and human tragedy overhangs, like the shadow of the hill on a hill-stream. But the crystal-clear waters of the spring still gurgle forward with occasional rays of the sun dancing on it; for life is endless and death only a step in this eternal recurrence.

Discussing the religious symbolism of primitive tribes and modern man's anxiety, Mircea Eliade has said that "Anguish before Nothingness and Death seems to be a specifically modern phenomenon. In all the other non-European cultures, that is, in the other religions, Death is never felt as an absolute end or as Nothingness: it is regarded rather as a rite of passage to another mode of being: and for that reason always referred to in relation to the symbolisms and rituals of initiation, re-birth or resurrection."

The Kondhs have a saying, Pahanahan tinjara, which literally means "By sharing, cat". This sums up the whole philosophy of the Kondh and his approach to life. While most primitive communities retain the intense intimacy of inter-personal, inter-family and inter-village bonds and are strangers to the lonely individual so common to modern urbanised society, these communal bonds are perhaps the strongest among the Kondhs. The entire village behaves as an integral unit, an organism. In joy and sorrow, in festivities and calamities, in privations and pleasure, in celebrations of rituals, dancing, hunting, clearing the jungles for podu or mourning a death--the whole village acts as one. This togetherness, this sense of belongingness is as ancient and as solid as the hills and as refreshingly dynamic as the gurgling hill-streams. It flows from a deeply felt sense of a mutual bond with the other members of the community and the village. The village is the unit of social organization; every individual is born into it, lives his life, suffers with it, dances and enjoys with it, and, when dead, becomes either a pointed stone (male) or flat stone (female) relic in its surroundings. The simplicity, frankness and naivete of the Kondh is reflected in his village organization. Rarely is a guest turned away from the village without being properly fed or looked after.